Nothing good happened during my career without risk. Some not-so-good stuff happened, too, but I have the satisfaction that I gave it a shot—whatever it may have been that I was risking at the time. At age 77, having no regrets feels good. It’s also true that nothing good happened without perseverance. There may be wisdom in knowing when to quit trying, but it’s more fun to morph your goals into something different than to bow your head in defeat. A Writing Career: Taking Risks, Persevering by Nan Lundeen.

Through it all, I kept writing.

I am the daughter of a school teacher and an Iowa farmer. Mother drilled into my head that education was vital for a woman because even if I married and chose to be a stay-at-home mom, I may have to support myself someday. That day came when I was the mother of two young children. My husband and I divorced. I had returned to school to earn a master’s in mass communications, believing that would boost my chances in the journalism world. In retrospect, I doubt that was true, but it boosted my self-esteem to return to school in my 30s and succeed.

Earlier, I had taken a non-credit writing course at a community college in Michigan where we lived and told my instructor, Sylvia Barclay; I wanted to be a journalist. I learned more from her than I did when I earned a master’s. I came up with an idea for a feature, and she sat with me at night after class in a café and circled sentences in my story: “This is journalism, and this isn’t.”

She advised me to climb the stairs at the local newspaper office, what time of day to go, and the exact words to pitch my story to the city editor. I was terrified, but it worked. He published my work. I built up a portfolio. An editor I queried in another town referred me to the publisher of two weeklies in an Indiana burg. I landed my first job as a writer and news editor there. Before I could start, I came down with pneumonia. But the publisher hung in there with me, and the kids and I eventually made it to Indiana.

The same process worked for me again and again. I invested in a good camera and added photography to my skill set to illustrate my stories. I built on work that I had done to land the next job and the one after that. When I felt I had hit a dead-end, I quit a newspaper job and returned to freelancing, working as a stringer for one newspaper or another until I could compile a strong enough portfolio, to move on.

When I was stuck in a position I hated, I’d resolve to write my way out of it. That meant at times returning soda bottles for enough change to pay for lunch. It meant going without health insurance for myself. The kids were covered under their dad’s policy. It meant once having an award-winning story stolen from me by an unscrupulous editor. I raised a big enough fuss that the editor’s boss paid me a fee with which I bought a much-needed new stove.

I learned that freelance writers have almost no power. I joined a writers’ union, which gave me a bit more confidence and some practical help, such as negotiating a book contract. In the end, I didn’t need contract advice because the risk I took to borrow money and write a novel mid-way in my career fell short. Still, I’m happy I let myself try. I would have regretted not giving it a go.

When my kids were in middle and high school, I suffered from deadly boredom working for a daily newspaper in a mid-sized Michigan town. A friend encouraged me to come to the East Coast—she would put me up at her Manhattan apartment until I found a job. I flooded newspapers in Massachusetts, New York, and Connecticut with resumes and copies of my best work. Wangled appointments with editors.

To drive out there, I would have to cross bridges. I had seen an often-replayed video of a bridge buckling somewhere in the Northwest and cars plunging into a river. My wise daughter, Jennifer, said, “How likely is it that Robert Redford will knock on our door?” She assured me it was just as likely that a bridge would collapse while I was driving over it. She gave me a new image—the fabulous, handsome actor at my door.

The kids shuttled to their dad’s for the summer; I loaded my Honda Civic with resumes, my portfolio, and a thrift store blazer and drove east. Crawling across a high bridge over a section of Lake Ontario, I gripped the wheel and repeated, “Robert Redford! Robert Redford!” Robert and I made it. Once again, the freelance articles landed me a job, this time in Bridgeport—at what was one of the largest-circulation newspapers in Connecticut.

Sometimes, I had to fight to keep a job. A short time after I started at Bridgeport, a pair of editors kept changing my copy by editing errors. The officials in the small town I was covering were livid. And who is going to believe, “My editor added those errors to my story?” Fortunately, there were two papers under one roof. I worked on the afternoon paper. The morning paper also used my work and kept it accurate.

I envisioned getting fired and my son Jeff and me living out of the Honda Civic. My daughter had stayed in Michigan to finish high school. Scared, but seeing no other option, I cut out the articles to show the accurate and error-ridden stories side by side. I made an appointment with the managing editor and the two copy editors. Sitting at a conference table with the three men, I laid down the pages one by one. The ME was shocked. He would never have believed me without proof.

Over the years, other journalism work came my way—the newspaper I retired from was in Greenville, SC, where my present husband was an editor. Now in retirement, he is my writing companion—I write, and he shows me how to make it better.

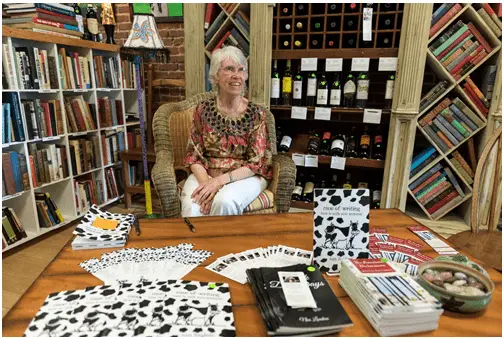

I’ve self-published a how-to-write book, Moo of Writing, which I dedicated to my mentor Sylvia. I’ve also published three volumes of poetry and spend my days writing poems, blog posts, press releases for an environmental organization, and pithy letters to editors about the climate crisis. During non-COVID times, I teach creative writing to children at a local Montessori school.

If I were to give the word or two of advice to people who want to write, no matter the field, it would be—challenge yourself, take calculated risks, and don’t let anybody push you around.

Nan Lundeen

Nan is the author of The Pantyhose Declarations, Black Dirt Days: Poems as Memoir, Gaia’s Cry, and Moo of Writing: How to Milk Your Potential. Visit her at www.nanlundeen.com.

Also read How I Came to do the Job of My dreams to be a writer

I love Nan Lundeen’s writing. This story relating her journey to where she is now, a published author and poet, is a testimony to her hard work and belief in her talent. An interesting and inspiring piece to read.

Nan, you continue to be an inspiration ~