Lizzie Harper

Lizzie Harper is a free-lance Natural History Illustrator. She works for publishers in the UK and abroad, environmental organizations, retailers, graphic design firms and undertakes commissions for private individuals. She attended Bournemouth College of Art & Design (specializing in natural history illustration) after getting a Zoology Degree from Bristol University and remains a keen amateur naturalist and botanist.

Recent jobs include illustrations for David Attenborough’s “A Life on Our Planet,” wood ant illustrations for an identification guide, a series of coastal flower stamps for Jersey Post, some fold-out leaflets for the Field Studies Council (FSC), packaging illustrations for both a pet food company and a BCD vaping firm, plus the illustrations for “The Tree Forager” by Adele Nozedar, and “30 Animals that Made us Smarter” BY Patrick Aryee.

She has exhibited her work in the UK and internationally and occasionally teaches natural history and botanical illustration courses. She lives very happily in Hay on Wye in Wales with her husband and children, working from her garden studio, and is currently working on sketchbook studies of invasive plants for a client in Iceland and the illustrations for “The Hidden Universe,” a book about biodiversity authored by the head of Kew Botanic Gardens.

Childhood and Education

As a child, I loved two things with a passion – animals, and drawing. I’d spend hours going through the compost heap looking for centipedes and worms, my bedtime stories were Gerald Durrell and books about insects by Farbre, and I spend ages drawing wicked witches and pretty ladies at the kitchen table.

As I grew, the passions were honed and combined. I got a microscope and started drawing the micro-organisms I saw swimming about in pond water. I volunteered at the Invertebrate house of the National Zoo (in DC, where I lived) every Thursday after school, feeding the octopus and telling the public about brittle stars and spider crabs. I drew all the time; still, lives of jugs and dishes, self-portraits, insects found dead on window sills…

I took APs (Advanced placements, A-level equivalents in the USA) in Biology and Art. In retrospect, the die was cast pretty early. I took a gap year and spent three months cataloging and collecting insects in the rain forest of Tanzania, and then another month studying sea turtles in Coast Rica.

I left DC to come to University in Britain, at Bristol, where I studied Zoology. I loved it, and my favorite subject was entomology. I loved dissections and loved drawing what I saw as I extricated the nephrons of a cockroach or the (inordinately long) penis from a limpet. However, statistics and an increased focus on genetics and biochemistry turned me off from Zoology. I didn’t want to spend my life running T-tests on data. I wanted to look at animals and plants and learn amazing and cool things about them.

Without knowing if it’d lead to employment or not, I went to art school. A happy year was spend doing printmaking, painting beetles, and drinking in the pub on Foundation. Then two more years doing an HND at Bournemouth College of Art and Design. The course didn’t teach me much in biology or techniques – many of the kids with me were painting enormous oils of tigers and elephants. I’d always prefer to do a tiny watercolour of lichen on a stone or a fly. However, it taught me discipline. We had to be at the desk and drawing by 9 am, no matter what. They also stressed the importance of keeping to your deadlines. Both of these life skills are invaluable in my day-to-day life.

Leaving college, I did a few unpaid jobs just to have published work in my portfolio. Computers and the internet weren’t massive (it was only 1996), so I tramped the streets of London visiting art editors who were stoically un-impressed and keen to rush off for a cappuccino. I was told that to make a career as an illustrator. I’d need to broaden my offering and paint jewelry and food. I chose not to listen and got a part-time job as a bookseller.

Early Jobs

The Wildfowl and Wetlands trust was my first big job. I had to quit the book shop and start working full days to produce the illustrations needed for their flagship new centre in London. Other jobs started trickling in. Lots were still with WWT, but I made sure they weren’t my only employer on the advice of my father. I sent off innumerable postcards and letters to publishers. I built a rudimentary website. When it became relevant, I started using social media and working the hashtag #botanicalillustration, #sciart #naturalhistoryillustration, and #naturalscienceillustration very hard. I advertised in industry annuals like the Directory of Illustration. I joined the wonderful Association of Illustrators.

Work started coming inconsistently. I worked fast and hard. I never missed a deadline. I accepted that the client is always right. I learnt about protecting my rights. I got better and better at self-promotion. I started doing grown-up things like negotiating fees and questioning rights grabs in contracts. Within five years, I was consistently full-time, and it’s stayed that way. I’ve written a blog about resources and advice for people thinking of starting as a freelance illustrator, which may be3 of some use: https://lizzieharper.co.uk/2017/01/starting-out-as-an-illustrator-advice-and-resources/

Problems Along the Way

But it’s not always been easy. I was caught copying a photo without permission on one job before I understand copyright infringement. The entire job (illustrating a calendar) collapsed under me, although I’d done 90% of the work, and I was unpaid. Some jobs end up being enormously time-consuming, and I’ve had to get used to working till 2 or 3 am a few times a month. This was something of a shock in the early days. I’ll always push to extend a deadline to twice the time I expect the job will take. That way, there’s elasticity if the client starts adding to the workload or being pernickety.

Rejections are still painful. Every year I apply for the World Illustration Awards. I tend to get short-listed one year in five. Some of the best work I’ve done doesn’t even make the long list. This is a setback I still struggle with, although it has no bearing on the incoming jobs. Another rejection was when I lost out to the wonderful Julia Trickey, another botanical illustrator. We were trying to get the commission to illustrate postage stamps by Royal Mail and do several trial pieces. Even though I got down to the last two, losing out at the final hurdle didn’t feel lovely. (I now know Julia well, and credit is due, her stamps are STUNNING!)

How I Work: Process and Challenges

The nature of being a freelance illustrator is that you literally work on hundreds of jobs every year. Accept the job, thrash out a contract and fee, get the brief, do a pencil rough, get the go-ahead, finish the illustrations, invoice for the job, and move on. Inevitably, I forget lots of the work I do, although I keep a rolling CV with every job I’ve ever done on it. It currently stands at 45 pages long and is (obviously) never sent out to clients. No client has ever asked to see any of my academic qualifications or my CV, to be fair. You have to travel on the quality of previously published work.

Challenges include finding correct references for tricky species (like mosses). Having a network of people in the scientific community is invaluable because they will often go out of their way to supply specimens and advice. Collecting a list of reliable online sources is important, too, as wildlife photographers are generous enough to grant permission for you to use their images for reference. You need to be able to communicate clearly with clients, and my Zoology degree is useful here. Marketing is yet another challenge. It’s monumentally dull but vital. Regular uploads to websites, social media platforms and paying for pages in Illustration annuals is ongoing.

I’ve also had some peculiar jobs, which saw me being reported to the police by a nude neighbour, lying on my stomach in a field of frisky buffaloes, and being asked to paint scabs.

Highlights

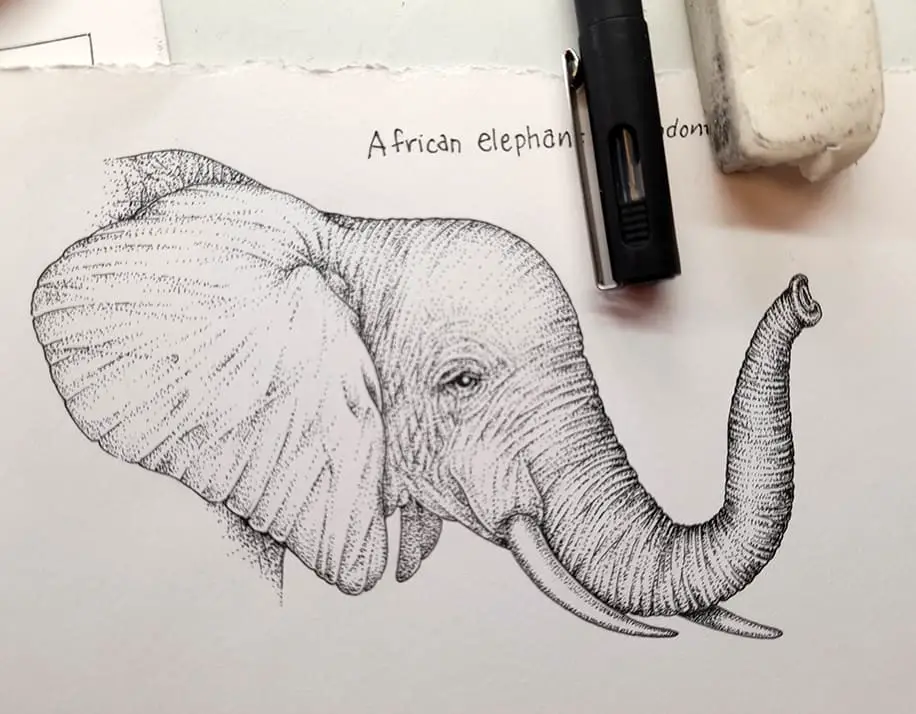

There are tons of jobs I’ve been lucky enough to get which have made me happy, but none have topped illustrating David Attenborough’s “A Life on Our Planet” last year. Eight pen and ink illustrations for a life-long hero. It was a dream job. Another lovely relationship has been with jersey Post, illustrating series of postage stamps. I’ve done beetles, fruits and berries, coastal flowers, roses, trees, and dragonflies. Seeing your work on a stamp feels great, and the lead times on these jobs are very long – an unusual treat in the industry.

How I Got High Profile Commissions

So how do you get these jobs?

It’s to do with being under the right noses at the right time. A big part of this has an obvious online presence. If you google “botanical illustration,” my name pops up within the first few pages. This is massively helpful. Work on your relationships with past and current clients, be an excellent and diligent worker, but also funny and friendly. After a job is done, be sure to keep yourself in their minds by sending targeted Christmas cards and the occasional email. Not only will this remind them of you for future jobs they might be commissioned, but they may well pass on your details to others in the industry. Word of mouth and personal recommendations cannot be bettered. Illustration annuals are helpful too, and some companies give information on potential clients (Yodellist, Bikini Lists), so you can present them with work samples. I also visit events like the London Book Fair, where I sit and illustrate in person, have meetings with art directors, and generally try and do some networking. I hate this side of my job, but it’s the price I have to pay to get the work I love doing.

Keeping Up to Date with my Industry

I keep up to date with what’s going on mainly through the Association of Illustrators, a beneficial organization. They provide tailored advice and events, promote illustrators’ work, and fight your corner when it comes to tussles with clients. They’re a great way to keep tabs on what’s happening in the industry.

Another good organisation is the Guild of Natural Science Illustrators (GNSI). They tweet job opportunities and have a wonderful and vibrant online community of sciartists. They also run an annual conference which I’m yet to visit but hope to someday.

I also take natural history courses to improve my knowledge. Weekend courses on shoreline ecology; day workshops on identifying grasses, bats, or snails; online sessions discussing beetles and meadow ants… Lots of these are offered by Field Studies Council and are highly enjoyable as well as professionally useful. They’re also (yet another) opportunity to network with future potential clients.

Other Income Streams

You may find that there’s not enough illustration work coming in to pay the bills (the industry is notoriously badly paid). Teaching, either in person at workshops or through online web platforms such as Patreon, can help. These work better if you already have something of a “fan base” who want to learn from you. It’s also a good idea to collaborate with other organisations such as Wildlife charities, Botanical gardens, or adult learning centres. This takes away a lot of the pressure of setting everything up.

I also sell my originals (and do prints of originals) and do exhibitions. As the illustrations have already been paid for by a commissioning client. I can afford to put low prices on them. This brings in quite a bit of extra cash and also prevents me from drowning in piles of moldering illustrations!

Alternatives to Freelancing

If you have set your heart on being a natural history or botanical illustrator; but feel weak at the thought of all the marketing, contract negotiation, pricing, social media, and networking, there is the option to look for an agent. Agents will do all of this for you, and find you jobs, for a fee. I believe they can also be very supportive psychologically.

I’ve never had an agent as I know you need to share your existing clients with them, and I don’t feel able to hand over the many personal relationships I have with people I work with to a third party. But if you’re starting, I think it’s well worth considering, not least because they tend to get better prices for work than an individual freelancer!

Is being a full time Natural History Illustrator a good job?

Well, yes. I am utterly passionate about the work I do. I love it. Every new commission feels like opening a gift. It excites me to see what species I’m being asked to draw next. I look forward to going to work every day, and not many folks have that luxury.

The hours can be insane, and the pay isn’t great (a good year sees me take £30k and I’m pretty well established). It can be hard to feel confident if the work dries up. You need serious self-discipline and real flexibility to adapt to the clients’ needs. You also need to be good at time management and juggling jobs without missing any deadlines. And be totally self-motivated.

But is it worth it? I love my job, and I love the life it gives me. Hell yes, it’s worth it!